Everyday violence in Thailand: Preliminary findings by MOVE research

Written by Nop Tephaval and Janjira Sombatpoonsiri

On 3 August 2022, two teenage gangs clashed in a gunfight in a public parking lot in Thailand’s northeastern province of Ubon Rachathani, killing three persons and injuring at least four. Reportedly at each other’s throats for years, the rival gangs used assault weapons, a movie-like shootout scene that frightened bystanders. #UbonShootingspree trended on Twitter overnight. Despite this public outcry, incidents like this occur regularly in Thailand to the point that they became normalised.

This contour of everyday violence adds to the intensity of existing armed conflicts in Southern Thailand and socio-political tensions in other parts of the country. Tabloid newspapers and online outlets report violent crimes and armed skirmishes day in and out. Nonetheless, we still lack a systematic database that offers cross-sectional and longitudinal patterns of organised violence across Thailand (with the exception of Deep South Watch which monitors the southern conflict). Without any systematisation of data that is available to the public, our understanding of violence trends in Thailand remains fragmented. We tend to view violence featured in major events such as the Southern insurgency and political protests in Bangkok as separate from everyday violence like the gang-based crimes described earlier.

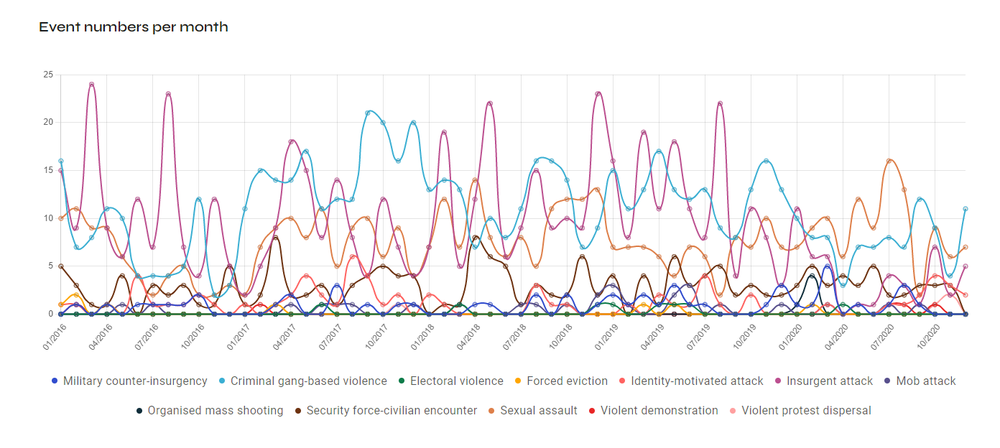

The Monitoring Centre on Organised Violence Events (MOVE) at the Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, addresses this gap by creating one of the first national online databases on “organised violence”. We define this notion as an event; 1) that involves the instrumental use of physical violence by individuals against other individuals; 2) in which perpetrators reportedly plan to purposively inflict violence on others. We focus on 13 sub-types assumed to capture key patterns of nationwide organised violence. These are criminal gang-based violence, security force-civilian encounters, electoral violence, forced evictions, identity-motivated attacks, insurgent attacks, military counterinsurgency, mob attacks, sexual assaults, terror attacks, violent demonstrations, violent protest dispersals, and organised mass shootings

Other than event types, we code basic profiles of perpetrators and victims, and dates, sites, and times of occurrence. Our period of observation in this first phase is from 2016 to 2022. Our sources of data are an online archive of five national newspapers (Bangkok Post, Khao Sod, Thai Rath, Manager, and Matichon). The year 2016 was selected as the base year of observation because it marks Thailand’s adoption of the new constitution after the 2014 military coup. In this way, we can control closed political space as a factor that might impact news reports. Our preliminary findings presented in this article are based on the data from the years 2016 to 2020.

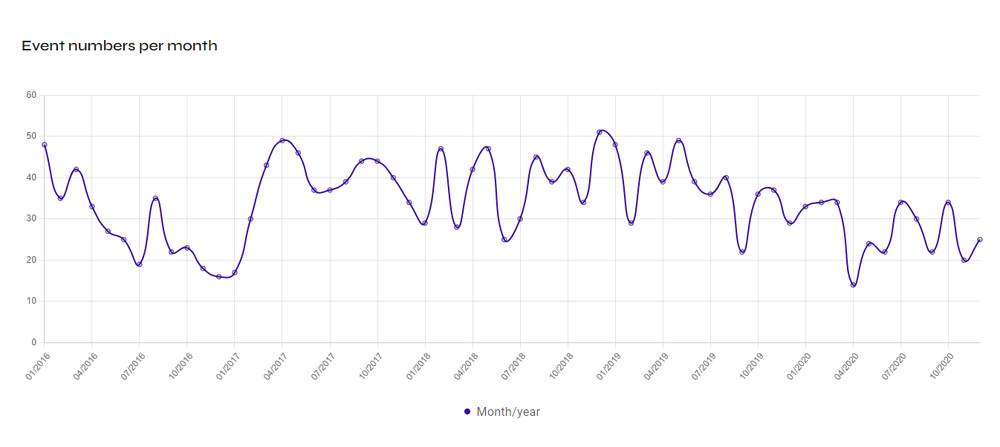

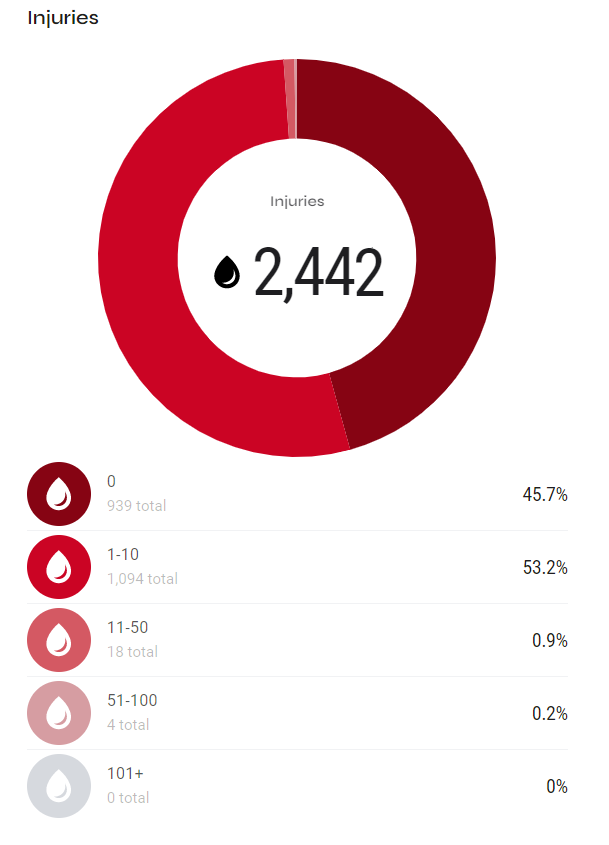

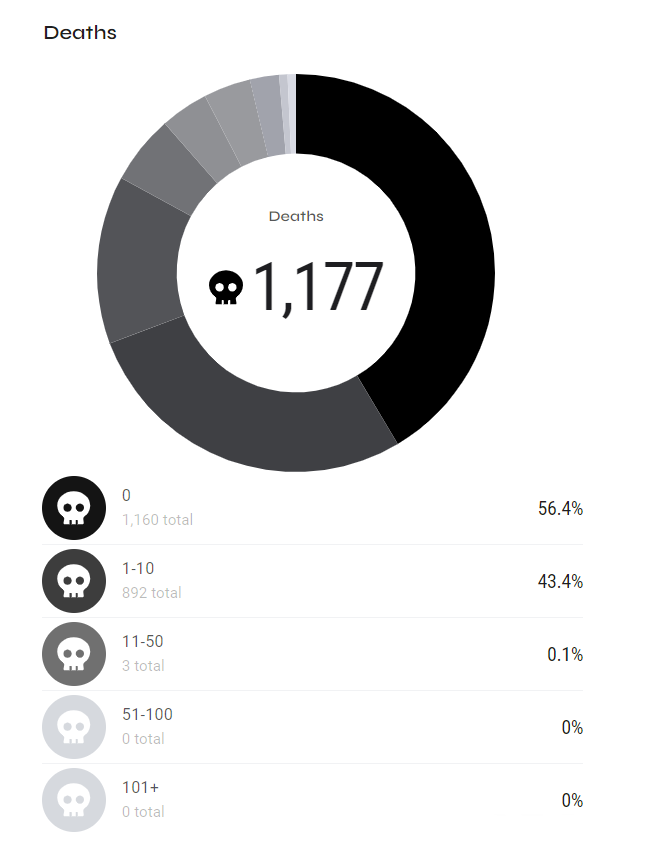

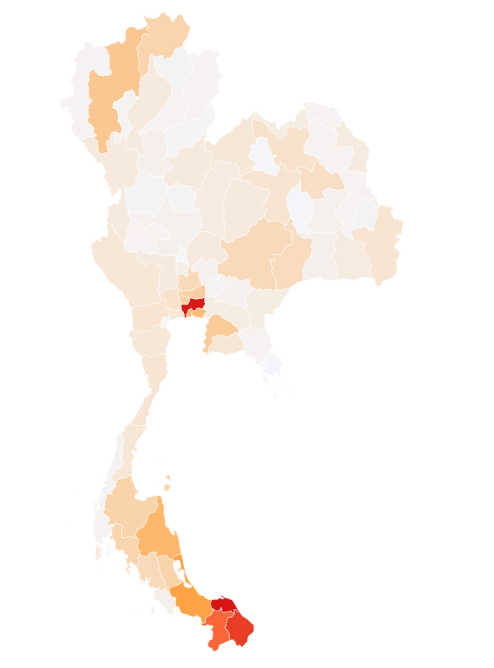

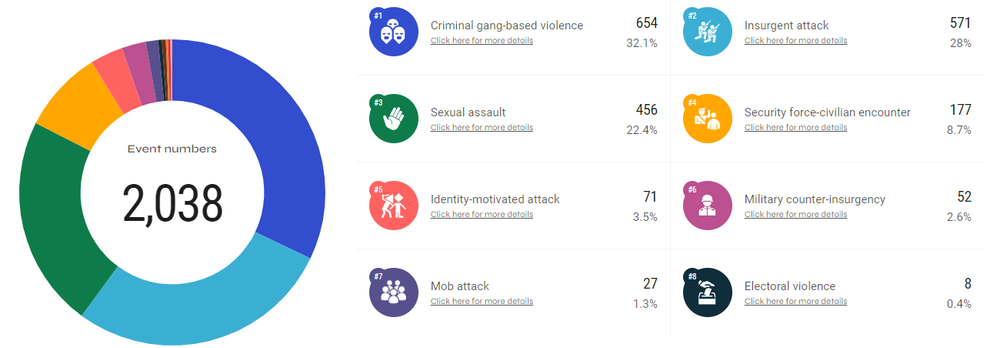

We coded 2,038 events over the course of five years. The number of events reached its peak in December 2018 when our system recorded 51 organised violence events in that month (Figure 1). This is possibly due to the confluence between gang-based crimes and insurgent attacks in the south. Most incidents (53.2 percent) injured between 1 and 10 persons (Figure 3), while 43.4 percent of the incidents killed between 1 and 10 persons (Figure 4). The occurrence of violence was concentrated mostly in Bangkok, Pattani, Narathiwat and Yala in that order (Figure 5).

Out of 2,035 events we coded, criminal gang-based violence (654 events or 32.1 percent) constitutes the most common sub-type of organised violence. Second to this is insurgent attack which mainly occurs in the deep south in which conflicts between insurgent movements and the Thai authorities came to a head (Figures 6). Our data contrasts with growing domestic and international concerns that southern conflict may be a bastion for violent extremism. Religious extremism, stemming from both Malay Muslim and Buddhist communities, may increasingly characterises the protracted conflict. But the coupling of violence and extremism in the south has not overridden criminal gang-based violence in Bangkok and upper southern provinces.

Our database shows the rise of collective violence between groups of individuals who self-identify with “micro communities” such as vocational schools, criminal gangs, and villages. When one group attacks a member of the other group, the latter seeks to retaliate by escalating physical attacks against members affiliated with the other group, thereby triggering a vicious cycle of continuous attacks. So far our data does not include factors driving this type of organised violence as the most prominent trend, but we can speculate based on and development studies literature that the proliferation of “micro-scale of violence” reflects a crisis of public trust in the justice system that is possibly related to weak rule of law. That is why parties to micro-scale conflicts tend to take matters into their own hands, relying on the “kangaroo court”. Furthermore, marginalised populations, especially young children, are encouraged to develop the necessary skills conducive to participating in “the culture of gang-populated areas”. This propensity increases in light of inequality, social exclusion and youth unemployment. The predominance of criminal gang-based violence coincides with our data regarding reported motivations in which personal and commercial drivers, whether calculated revenge or business rivalry, contribute to the clashes.

Where we could identify the perpetrators, we found that the involvement of non-state actors, including insurgents, individuals, and criminal gangs features prominently (78.5 percent). Perpetrators of some events are, however, identified as state actors mostly associated with the Thai security and administrative apparatus (Figure 7). While it is difficult to determine whether this trend is shaped by our sources of data which might not necessarily report violence by state actors, it seems that the prominent role of non-state actors is concurrent with the regularity of criminal gang-based violence and insurgent attacks. These non-state actors usually commit violence in public and open areas including the street and public transport (50.6 percent). However, second to this trend is the occurrence of violence in private residential premises (Figure 8), which may be connected with sexual assaults and gender dynamics discussed below.

Sexual assault constitutes the third most common type of organised violence that we coded (22.4 percent). Where we could identify the age and gender of victims, they are overwhelmingly young females (90.7 percent) in the age range between 0 and 14 years old (47.1 percent). (Figures 9 and 10). In contrast, those reported to commit sexual assaults are overwhelming males (94.7 percent), who are between 25 to 64 years old (60.9 percent) (Figures 11 and 12).

Details of sexual assault cases can be gruesome, with perpetrators at times identified as close or distant family members of the victims. In other cases, the perpetrators are as young as 11 years old, while the victims can be as young as two or as old as 80. Some perpetrators abuse their social status such as monks to harass victims sexually. And many others claimed that they were state authorities to assert influence that prevented victims from reporting the abuses to the police.

These patterns tell us not only about gender but also the power dynamics of sexual violence in Thailand. In families, young and old members are considered powerless, subject to abuse by male members who are sometimes breadwinners. In society, persons with respectable social status or person of authority can induce obedience and fear into keeping victims silent. Ultimately, widespread sexual assaults, at least according to our data, reflect pervasive patriarchal structure and values in Thailand that partially underpins the tendency toward extremism that glorifies masculine militancy.

By zooming out on major conflict cases such as the deep south, our data shows diverse shapes and forms of organised violence in Thailand. On the surface, some of these may not be necessarily driven by extreme political or religious ideologies assumed to disrupt social cohesion. But everyday gang-based crimes that dominate the landscape of organised violence in Thailand reflect broader structural and cultural predicaments. For one, it appears that eroding rule of law and collective identities based on micro-communities contribute to this rise. In addition, socio-economic marginalisation and preexisting gendered power relations may explain why young men are the predominant group of perpetrators. Most importantly, the regular occurrence of these crimes shows how micro-conflicts are often channeled through violent confrontation as parties to them potentially bypass peaceful alternatives of dispute settlement.

Based on our preliminary data, we suggest policy interventions that “de-normalise” everyday violence and address how this first step is pertinent to fostering human security in Thailand. Increased resources should be geared toward strengthening judicial mechanisms to build public trust in them, and alleviating the livelihoods of those from vulnerable communities. More support should be rendered to civic initiatives that promote peaceful conflict resolution at the macro and micro levels and stimulate public discussion regarding gender as well as social norms that sustains the culture of violence.